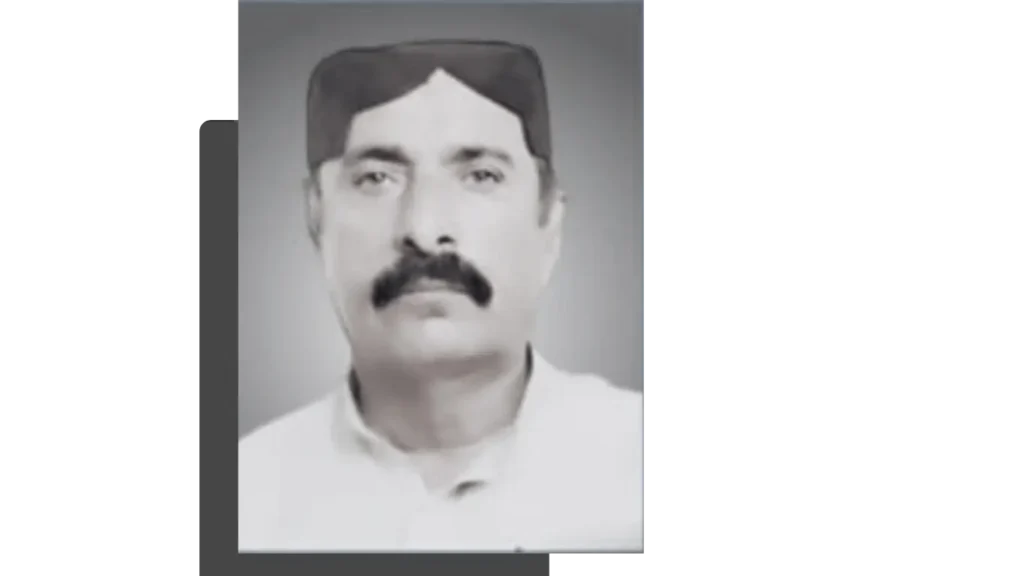

Gwadar’s Century Old Thirst- Akhtar Malang

Akhtar Malang When I first became aware of the world around me, I remember hearing the chants, “Give us water or leave the chair.” As I grew older, one thing became clear , in my hometown Gwadar, water was rare. Back then, every ward had a government water tank. In our neighborhood too, there was one. Every evening, women would gather around it, balancing pots and buckets, waiting patiently in line. Life in Gwadar depended on those tanks; they were our only source of hope. I still remember how our senior classmates used to protest during school assemblies. They would boycott classes to raise their voices against the water crisis. Those protests often disturbed our studies, but the problem was too serious to ignore. The shortage of water in Gwadar is not new. It has existed for centuries. People often say, “A few days of moonlight, then darkness returns.” That is how it feels here. Once in a while, it rains and the dams fill up. For a year or two, life seems easier, and then the same struggle begins again. Our elders often spoke of the old Gwadar, a town without electricity, roads, or modern comforts. Yet it was full of friendship, kindness, and humanity. But even in those simple times, water was hard to find. They used to tell stories about three wells at the foot of Koh-e-Batil. People would climb the hill with gallons tied to donkeys. Others, young and old, walked long distances to fetch drinking water. Those wells still exist today, but they have fallen into decay and neglect. If those wells were cleaned and restored, perhaps sweet water could flow again. But Gwadar’s misfortune continues. In every government and in every era, the same problem returns. If it doesn’t rain for a year, the land dries up. Trees, animals, and people all suffer from thirst. When the crisis becomes unbearable, the authorities suddenly wake up. Old and broken plants are repaired. The Dasht Sentsar Bore is remembered. New bore projects are announced. Social media fills with statements and promises. But in today’s world, no country survives on rain or dams alone. Most use desalination plants to turn seawater into drinking water. Sadly, Gwadar — the heart of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, still lacks this basic need. People here still wait for rain or rely on water tankers. The world has learned to make life out of seawater, while we in Gwadar sit by the sea and remain thirsty. The world is moving forward, surrounded by comfort and progress. Yet our misfortune is that even today, women in Gwadar walk through the streets at dusk with buckets and pots on their heads, searching from house to house for water. When will our fate change?When will we stop crying over the absence of basic necessities?And when will we finally become a part of real progress, not just silent spectators watching others move ahead?